Folks who are interested in landfill diversion and reuse might be curious about the fate of the country’s many vanished buildings. Where have they gone? Predominantly to landfills and recycling, I regret to say.

“But wait,” you ask. “Don’t we have vibrant reuse businesses throughout the U.S.? And a national building materials reuse association?” Maybe. Read on and draw your own conclusions.

First, consider the size and condition of America’s deconstruction industry. We’re talking about established businesses, both profit and nonprofit, whose owners and managers work fulltime in deconstruction, the distribution of salvaged materials, or both. They include businesses that focus on architectural salvage as well as those, such as some Habitat for Humanity ReStores, that salvage or distribute utilitarian materials. I’m guessing there are only about 200 organizations (including 50 to 100 ReStores) in the entire country that could rightfully claim to be in the deconstruction business.

Those figures do not include businesses that salvage only lumber. Here’s why: Approximately 250,000 to 300,000 houses are demolished in the U.S. each year. However, over 40 million single family homes are remodeled each year, and 90 percent of those do not include significant quantities of lumber. Besides, lumber salvaged from houses is typically Douglas fir and southern yellow pine in dimensions of 2x4 to 2x8, which are too small for serious lumber-only salvagers. The majority of remodel materials consists of doors, windows, cabinets, appliances, lighting and plumbing fixtures, and these materials not only cost more than lumber, but contain two to 10 times more embodied energy (for an analysis of embodied energy by product, see https://thereusepeople.org/are-you-salvaging-lumber-only-why/).

Secondly, Build Reuse is the only national organization focused on deconstruction and the salvaging of building materials. It has 108 members, up from 50 a few years ago. However, the number of members in deconstruction and/or the distribution of salvaged materials is only 28. That means not even half are active deconstruction professionals. The remaining membership is comprised of cities, architects, designers and consultants.

What accounts for this lack of participation is primarily distribution. Distribution is the process by which a good or service passes through a chain of intermediaries to the consumer. For goods, distribution channels include aggregating products, packaging, warehousing, transportation, disaggregation (breaking bulk) and pricing. How a product is moved from origination to buyer is a key element in marketing. (I was willing to pay the delivery price of the last new car I bought. However, living in San Diego, I was unwilling to pay the delivery price of a telephone booth glass door embellished with the Bell logo that I purchased in Minneapolis 10 years ago. I gave it to a good friend.)

Now state and local governments from coast to coast, border to border, are passing legislation requiring diversion from landfills. Meanwhile, many landfills are closing. I know of at least one state with no construction and demolition landfills.

Compare the cost of opening a new landfill with that of a medium size warehouse (20,000 square feet plus a 10,000 square-foot lumber yard, market rental rate $550,000 to $600,000 per year). Virtually any growing city with a population of one million people owns property of this size that is currently unutilized or underutilized.

The U.S. is losing billions of dollars in reusable materials because states and cities fail to do the right thing by entering into private-public partnerships to provide warehouse space for collecting and distributing salvaged materials. In such a partnership, the private operator might have zero rent the first year, with reasonably large increases in each of the following years and an agreement period of five years, with successive five-year options totaling 15 to 20 years.

Mandating landfill diversion without sound distribution alternatives is financially wasteful and deprives hardworking constituents of valuable but inexpensive materials.

Where have all the buildings gone? I guess the real question is, “When will they ever learn?”

As a Regional Manager for The Reuse People (TRP), I help to fulfill the organization’s mission to reduce building-materials waste, an involvement that stems from my interest in the varied benefits of building-materials reuse, and in my enthusiasm for improving local communities and the environment.

Having your home remodeled, or torn down, for a rebuild is a daunting task. For sure, it is disruptive to the normal ebb and flow of daily routine. There are many details to keep track of, large and small.

Adding to this challenge, TRP asks you, the property owner, to consider salvaging the building materials as an alternative to having them end up in the local landfill. Replacing demolition with deconstruction for a remodel or rebuild certainly adds a wrinkle to the project. I’d like to share why entertaining and embracing that wrinkle is worthwhile.

Anyone who scans the news on a smartphone app, or listens to or watches traditional news, will at some point be exposed to a story on our environmental challenges. The news always sounds overwhelming, the hurdles insurmountable. But the truth is, we can make decisions and take actions that surmount those hurdles. Our actions may not be as visible as the STOP sign on the nearest corner, but their impact is real. And our neighbors, as well as the planet, benefit.

For starters, every fixture we can redirect from the landfill is significant. Landfills detract from the quality of the air, water, and soil. Salvaging a vanity cabinet, a refrigerator, or a ceiling light reduces further contamination. By actively pursuing deconstruction, we are improving the quality of our lives, our neighbors’ lives, and the community at large.

Furthermore, reusing building materials puts community members to work. Employed citizens are notable assets. They buy local goods, develop skills to assist friends and family, and raise the vitality of entire neighborhoods.

Salvaged and donated materials boost the quality of our living spaces. An apartment owner who wants to freshen up a rental unit when it turns over can upgrade economically by installing used materials. Both the owner and the renter benefit. Property owners on limited budgets can enhance their homes and living conditions with used materials.

As a donor of used building materials – a responsible owner who chooses deconstruction over demolition – you need to “right-size” your expectations. Although your benevolence will not be recognized in a print or online news article, what you will possess is the awareness that you have reduced landfill waste, moved air, water and soil quality in a positive direction, and improved the lives of people in your community – all outcomes to be truly proud of.

In my distant days as a partner within Creative Business Strategies, I focused on raising money for entrepreneurs and developing new technical and scientific breakthroughs, including silicon chip manufacturing, machine learning software and robotics. Today, technology has passed me by so quickly that I struggle trying to permanently increase the font size of my Outlook emails. Since 1993, I have been engaged in deconstruction, which, being part of the construction industry, whose size represents over 4.3 percent of the US GDP and is our country’s 12th largest business sector, is still deeply rooted in 19th century technology. However, in the past 30 years, more and more technology and science have impacted the building materials corner of the world.

In TRP’s first years I was fortunate to be at a conference where the speaker was passionate about reuse and, in particular, building materials. This Birkenstock wearing, roll-your-own smoker and last of the hippie generation saw deconstruction as an employment vehicle for an underserved population – so much so that the use of a generator was a no-no, since it reduced workers’ hours.

At about the same time, I visited some old Northern California port buildings that were being deconstructed and was amazed at the dangerous conditions of the site and the lack of simple head gear, let alone boots, gloves and safety glasses.

Now move forward to the late 1990s and the pilot deconstruction of four buildings at fort Ord. Not only were all types of PPE required, but during the abatement of asbestos and lead, special suits and breathing apparatuses were required, and abatement workers received blood tests before and after abatement work was performed. Yes, safety is very scientific.

A quick jump to 2001, and Jon Giltner’s invention and introduction of the Nail Kicker®, a handheld pneumatic denailing tool. Jon is a structural engineer by education and profession and the president of Reconnx, Inc. (www.NailKicker.com). Not only does this tool save lots of arm muscles, but in my experience has reduced total deconstruction labor costs on a typical 2,000 square-foot house by at least one full crew-day.

The goal of deconstruction is to save the maximum amount of building materials for reuse, but ultimately, each project has leftovers for recycling, such as metals, glass, wood products and concrete. While concrete recycling dates back to the 1980s, it has only been within the past five to 10 years that robotics have replaced human hands on the sorting lines of major recycling centers, transfer stations, and landfills.

Thinking lumber salvage, deconstruction and, now, robotics, I agree (but just for today) with Urban Machine, the brain child of Eric Law and his little band of young engineers: This machine, now just moving from testing to manufacturing, is a giant step forward in the deconstruction and larger construction industries. It is built to remove surface materials (dirt, debris, paint, etc.) and then nails and other embedded metals. And it is especially suited for larger dimensional lumber, such as 4x4, 4x6 and larger. It may also be used on 2x material. (www.UrbanMachine.com).

One small step for evolution; one giant step for deconstruction.

While preparing to write January’s Velvet Crowbar, I decided to do some internet research. When I conducted a Google search on Design for Disassembly, the first full page of references included the titles, “Design for Disassembly and the Environment,” “Design for Disassembly and Deconstruction: Challenges and Opportunities,” “Design for Disassembly: Themes and Principles,” “Design for Disassembly (DfD),” and “What Is Design for Disassembly?,” followed by eight additional listings. All were scholarly and quite informative; however, none cautioned the use of glue or spray insulation.

This is nothing new. I’ve been reading articles like these for 30 years, as both builders and demolition associations awakened to the benefits of building-material salvage, deconstruction and reuse. However, very few have questioned how to stick things together for easy removal. And today, hundreds of internet videos show various methods of building and repair work using techniques and products that defy salvage and reuse. Such disregard is not only puzzling, it’s shameful.

About 10 years ago, TRP deconstructed a home in Aspen. The owners wanted the random plank hickory floor (about 2,000 square feet) salvaged for reuse in their new home. Unfortunately, it was glued to the subfloor. And to make matters worse, the plywood subfloor was glued to the joists. The general contractor suggested that the flooring and subfloor be cut out together in 4x8 foot sections, and the owners agreed. With considerable effort, this process was accomplished, but even with careful cutting we lost most of the 2x10 joists.

TRP recently completed a 5,000 square-foot deconstruction and ran into this problem again. The first floor had been remodeled, and the replacement wood flooring included walnut in the main portion of the house and maple in the bedrooms. Both were glued to the 1&1/8 plywood subfloor. Consequently, we lost both the finished floor and the subfloor. Fortunately, the subfloor was not glued to the joists. From the second floor, which was not remodeled, we salvaged 2,000 square feet of oak flooring and the plywood subfloor.

As a substitute for glue, think about using 15 pound felt or, better yet, cork as an underlayment. Even better, how about floating floors of engineered wood? It is no more expensive, yet easier to install and much easier to repair (try repairing glued tongue–and-groove flooring).

Then there’s the problem of spray insulation, which complicates the salvaging of windows when it is sprayed between the frame and studs. Time spent cleaning off this stuff doubles the amount of time spent salvaging the windows. Besides the windows, all we are left with is a pile of spray insulation, which even after a thousand years will still be there —in the landfill.

Bricks are great and there is quite a market for used ones. But I do not understand why, in walks and patios, they are set in concrete. Concrete is like glue. With the same effort and less cost, bricks can be laid in sand, assuming it is properly prepared. Don’t even think about recounting the effects of ground movement or moisture as an excuse for using concrete. As a kid, I worked on a couple of long brick driveways in Cleveland using only sand as a base, and the driveways lasted over 40 years, in high humidity, lots of rain and below freezing temperatures (which, by the way, is one reason I now live in San Diego).

Several years ago TRP made an invited foray into Chicago, establishing The ReUse People of Illinois. Within a few years that office became a leader among our 12 regional locations, thanks largely to Illinois Regional Manager Ken Ortiz, who also currently serves as TRP board chairman.

TRP has now begun a second venture into the Midwest – this time to Michigan. The spark that led us there a couple of years ago came from Rex LaMore, Director of the Center for Community and Economic Development (CCED) at Michigan State University. He asked TRP to become an advisor to the MSU Domicology Consultive Panel (see www.domicology.msu.edu). Domicology is defined as “the study of the economic, social, and environmental characteristics relating to the life cycle of the built environment.

Late last year, CCED Project Coordinator Nathaniel Hooper proposed that MSU, Muskegon-based American Classic Construction (www.AmericanClassic.us) and The ReUse People form Michigan Deconstruction Collaborative, an organization focused on providing deconstruction to building owners in that state. The collaborative trains both contractors and workers in the art and science of deconstruction and received a grant from the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) to conduct its first worker training.

With the direction and assistance of Tim Burgess of the Muskegon Land Bank, the collaborative has secured a house to be deconstructed by students during the first training, scheduled for April 2023, and will utilize additional houses owned by the land bank for future trainings. Participants will include two supervisors from American Classic, a TRP Certified Deconstruction Contractor, and up to ten unemployed workers who will be offered full-time positions with American Classic upon successful completion of the course. After a second successful training, the two supervisors will be certified by TRP to conduct their own trainings in Michigan.

During the training Nat Hooper and MSU Domicology students will detail sustainability points by calculating the carbon units and embodied energy saved by salvaging materials. The team will also conduct a comprehensive assessment aimed at understanding current market conditions for demolition and renovation/remodeling in the region, allowing for an estimation of the potential volume and value of recoverable materials available within American Classic’s service area. This information will help to scale the collaborative’s activities going forward and will also serve as a focal point to help educate the public regarding the wide array of environmental, economic, and social benefits that deconstruction offers.

Between now and the training, Nat and his team, in conjunction with American Classic, will promote and investigate deconstruction opportunities throughout Michigan and will offer deconstruction to residential and commercial building owners as an alternative to traditional smash-and-dash demolition. All salvaged materials will be donated to TRP, and building owners will receive documentation of their generous tax-deductible donations.

To ensure a sound, sustainable and circular building-materials market, all salvaged materials will remain local and be available for purchase through the retail warehouse arm of the collaborative, which will offer high quality reusable materials for cents on the dollar.

Six months have passed since I wrote about the importance of commercial deconstruction and materials salvage, in an earlier e-letter. Since then, developments in this arena have been explosive.

February and March: At the request of StopWaste.org and the San Francisco Department of Environment, TRP participated in a study concerning the viability of creating a relocatable distribution center for commercial materials. The architectural firm Gensler with Madrone, a commercial deconstruction company, spearheaded the study, with TRP providing research and information relative to current practices. The results were published in the “StopWaste book” (the Book). The idea was to rethink the market for reused commercial materials, review relevant supply chains and consider distribution options. More on this below.

Late February: I received an email from a contractor who wanted TRP to help his client identify the salvageable materials in several buildings, totaling 1.1 million square feet. With assistance from Deconstruction and ReUse Network (DRN), TRP produced a report identifying all reusable materials for which homes could be found, with specifications stipulating how each of the materials would be removed, protected and palletized. The report was delivered three weeks later.

July: TRP was asked to replicate the previous process on two more commercial projects: a 10,000 square-foot building in Palo Alto and a 275,000 square-foot office building in Redwood City. On the first project we completed a survey of the materials to be salvaged for reuse; on the second our proposal is being considered by the construction manager.

August: We are currently preparing a proposal for the developer of two commercial office buildings of approximately 25,000 square feet each.

Research for the Book (see above) found that, in most cases, when undergoing renovation, commercial building structures remain in place while their interiors are demolished and rebuilt for new tenants. Consequently, materials available for reuse are limited to interior fixtures — doors, cabinets, plumbing, some lighting, flooring, furniture, etc.

In the San Francisco Bay Area it is not uncommon to find three and five-year leases, as opposed to traditional leases of 10-plus years. Consequently, lease terms often require the lessee to leave the premises in “warm lit space” condition, meaning that any tenant improvements must be removed by tenants when they leave. So even though the building itself is not reduced to rubble, there is a constant turnover of tenants and a continuous flow of used or tenant-improvement materials. The Book presents a case for the temporary storage and distribution of these materials, or, borrowing from Ernest Hemingway, “A Movable Feast.” See: StopWaste Book.pdf.

Until large distributors and reusers enter the field of commercial deconstruction, TRP is looking for partners who can assist with current logistical challenges. To date these partners are architects, deconstruction contractors, and distributors of salvaged building materials and furniture. Meanwhile, we are talking with various stakeholders about forming a public-private partnership to acquire permanent real estate for the storage and distribution of materials for which immediate users cannot be found.

Earlier this month I was invited to the historic town of Victoria to give two workshops for a range of people tasked with implementing the city’s newly passed Deconstruction Bylaw. Audiences included building, demolition and deconstruction contractors, house movers, city personnel involved in the bylaw’s oversight, receivers and distributors of salvaged building materials and construction managers.

These were the city’s instructions:

• Review in detail the reporting requirements that contractors must meet when verifying the materials salvaged from each project.

• Outline the benefits of deconstruction over traditional smash and dash demolition.

• Detail the procedures, from the initial deconstruction survey through the delivery of salvaged materials to the recipient.

• Explain how to preserve the value of salvaged materials once removed from the structure.

• Demonstrate the nexus between deconstruction and historic preservation and adaptive reuse.

• Summarize how an item’s embodied energy is saved through deconstruction.

Since 2017, Several Western Canada and US cities have passed, or are in the process of formulating, deconstruction bylaws. Those passed in Victoria and North Vancouver are more effective than most of the others I have encountered in either country. By effective I mean that 1) contractors must meet or exceed specific salvage weights, and 2) contractors who miss those targets face financial fines ranging from $15,000 to $19,500 per project.

Since waste diversion (zero waste) is the objective, I am at a loss to understand why any municipality would enact an ordinance, but be unable, or unwilling, to measure its progress. My personal management hero, Peter Drucker, often stated, “If you want to manage something you must measure it.”

For a bylaw to be truly successful, deconstruction contractors must be held accountable for their diversion quantities and weights. This requires some education. By this I do not mean they need to be trained in deconstruction. If today’s contractors need to be taught how to remove a window, door, cabinet or framing member, they should not be allowed to call themselves contractors. What they must learn is how to protect a component’s value after it has been removed and during shipping. This knowledge is generally not in a contractor’s purview and simple training in value preservation is best.

Furthermore, when a municipality requires deconstruction, contractors who have failed to meet diversion requirements should be banned. One of the homeowner’s major incentives for choosing deconstruction is the tax reduction earned by donating the used materials to qualified nonprofit organizations and receiving a Canadian tax credit or documentation of their US tax-deducible donation. If a contractor is not meeting the city’s requirements, then the owner is not donating the optimum quantity of salvaged materials, resulting in a lower tax benefit. After all, the homeowner is really assisting the municipality in achieving diversion goals by bearing the increased cost of deconstruction and should not be further penalized by using an incompetent contractor.

A fascinating Google alert recently landed in my in-box. When I read the title, “235-Year-Old Home Deconstruction,” the first thought that jumped into my mind was, Who would deconstruct a 235-year old home?

The home in question was originally built in approximately 1787 by Israel and Susannah Grant (a sister of Daniel Boone). Its final owner was, and I guess still is, a trust established by John and Dullia Drake. A grandson of the Drakes decided that since no one had lived in, or maintained, the house for the past seven years, the only way to preserve it would be through deconstruction and rebuilding elsewhere. Ideally, the house would be preserved by a live-in owner; however, neither a Drake descendent nor an outside buyer could be found to assume the task. Fortunately, the contractor hired to do the deconstruction was experienced in historic buildings and took the time to carefully remove and catalog all of the home’s original parts.

Deconstruction is one thing, but cataloging and mapping what went where, and how, is entirely different, and critical. The house had been remodeled repeatedly during its lifetime. The first substantial remodel occurred in the early 20th century, when all structural elements were covered over with contemporary materials. This redo was followed by several smaller changes over the past century to the point that the house ultimately attained the appearance of a Victorian two-story with all the frills.

Thankfully, the Drakes had an inkling what might be found under the one, two and three-plus layers of paint, paneling, drywall and plaster, so for them deconstruction was the obvious choice.

In TRP’s 29 years of deconstruction and salvage, our crews have often encountered older buildings where substantial remodeling concealed something of value. In 2007 we deconstructed a craftsman house in Napa and removed a wall that had been constructed right over a built-in buffet, complete with cabinet hardware and leaded glass doors. Fortunately the owner decided to preserve the buffet as opposed to ripping it out. If he had chosen to demolish rather than deconstruct, that beautiful buffet would have gone to the area’s vast graveyard—the local landfill—along with all of the other materials.

Other fascinating finds include a 1x12 oak subfloor discovered during deconstruction of an 1870s house in West Virginia, a twenty-dollar confederate bill behind a wall cabinet in an 1850 Kansas City house, still operational time-zone clocks behind a false wall in the Cincinnati Union Station, and a hand-drawn confederate civil war battle map drawn on a wall, and later covered over with wall paper, in a Georgia building.

As materials grow more expensive—especially scarce and high quality materials, such as historical elements, old-growth Douglas fir and wormy Chestnut—deconstruction becomes the go-to solution and is becoming competitive with traditional smash-and-dash demolition.

None of the “finds” TRP has experienced equal the revelation of Susannah (Boone) Grant’s home, but they clearly point to the need for a modest amount of deconstructive testing prior to demolition, especially on older buildings.

My journey from finance and investment banking, to deconstruction and building-materials salvage necessitated that I examine the historic, environmental and financial benefits of adaptive reuse. Admittedly, the projects I toured, read about and investigated were generally quite large and visually impressive. For example: Cincinnati’s Union station, Hong Kong’s New Arts Center, and The American Tobacco Company in Durham, North Carolina.

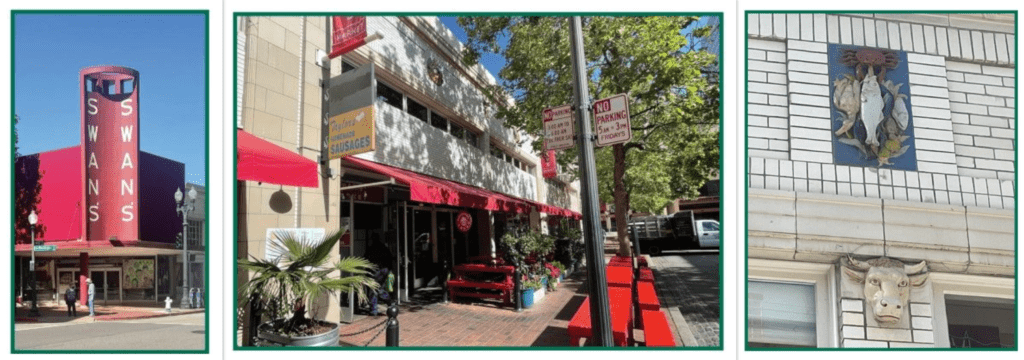

A couple of weeks ago I visited Swan’s Market in Oakland, California. From an age standpoint, Swan’s does not even come close to most adaptive reuse projects, since it was built as a two-story market in 1917 and closed in 1983. It’s an eye-catching two-story structure encompassing one city block from 9th to 10th, streets, and from Clay to Washington. The East Bay Asian Development Corporation, with support from the Oakland Redevelopment Agency, completed an adaptive reuse of the building in 2002, maintaining the name Swan’s Market.

Historically, in addition to a popular shopping venue, Swan’s was a social gathering place for locals and travelers. Today this same sense of community and socializing remains a key feature of the market. Swan’s is filled with individual purveyors of sea food, sausages, and baked goods, and also has a collection of eat-in and take-out restaurants featuring Indian and Caribbean foods, a noodle house, oyster bar and Japanese bistro, plus a deli, bakery, juice bar and specialty coffee house. Some of these have their own indoor and outside seating, and all share the garden and community tables.

The second floor encompasses several apartments, with indoor parking on the first floor. Add to this a menagerie of shops, including hair solons, barbershops, doctor and architect offices, and you truly have a community gathering place. All this in one small block.

Founder and entrepreneur Jacob Pantosky commissioned Oliver & Thomas Architects to design the building and, in 1921, architect A.W. Smith was hired for the addition on Clay Street. Between 1925 and 1927, architect William Knowles completed more additions. In 1940, Edward T. Foulkes designed the last expansion, Swan’s Department Store on the corner of 9th and Washington. All additions subsequent to the first construction continued the use of white glazed brick, steel awning windows and the outstanding custom terra cotta medallions that adorn the façade on the second floor. These colored medallions depict all types of foodstuffs, from meat to vegetables, to grains. The entire façade is original, as are most of the second-floor windows.

The takeaway here is that adaptive reuse dons many faces, and while large projects draw thousands of eyes, small, community-centric concepts also work.

When TRP launched some 30 years ago, I didn’t give a thought to commercial building materials. Eleven years later, after deconstructing elaborate sets from the final two Matrix movies, I still don’t remember considering commercial, and the same goes for the 20,000 square-foot commercial building at Northstar Ski Resort, which we completed two years later. Since that time, TRP has received a modest quantity of commercial materials from another company, Deconstruction and Reuse Network.

Still, in light of various deconstruction ordinances, and after conducting several webinars on deconstruction, building-materials salvage, Life Cycle Analysis and embodied energy, I’ve concluded that the future of salvaged building materials resides squarely in the commercial sector.

While the reasons are easy to explain, the path is torturous. With residential deconstruction, the cost of starting a deconstruction contracting company was, and still is, relatively insignificant. In hindsight, even the cost of starting a residential building-materials retail distribution center is not terribly consequential. Becoming a commercial deconstruction contractor is a bit more challenging. But the distribution of the commercial materials, when fully and properly executed, is truly daunting and will require tens of millions of dollars. Mr. Bezos, where are you?

Presently, several developments are encouraging commercial deconstruction.

First, over the past 30-plus years, customers have awakened to the benefits of buying and installing used materials: they are less expensive and usually of high quality, public interest in history, historic preservation and adaptive reuse is increasing, recent supply-chain shortages have put a crimp in the availability of new materials, and consumers are realizing that reusable materials are often better than new or recycled.

Second, many commercial materials, including lighting, cabinetry, carpet tiles and doors, are highly marketable in residential reuse.

Third, there’s demand everywhere for lumber and bricks.

Fourth, unlike the old days when we had to scrounge and dumpster-dive for enough materials to satisfy daily residential demand, today’s commercial projects yield abundant supplies.

At least 15 municipalities have deconstruction ordinances, or are in the process of enacting them. While 30 years ago such ordinances were unheard of, today we pretty much expect them. So, a lot less creativity is required to understand and accept salvaged commercial materials when we demolish, renovate, remodel or rebuild.

Managing the supply of used commercial materials is in itself a huge hurdle, and consumer demand can get fussy. There are approximately 10 to 15 doors in a single-family residence and 500 in a medium-sized office building. Suppose a buyer is looking for 543 identical doors and we only have 500. Since the buyer can’t find the other 43, they pass on the 500. Well, at least we have a ready supply in inventory.

But what do we do with the doors, store them? Where? What about code changes for fire rating, panic hardware or steel frames? How does a seller catalog the myriad specifications required by the commercial buyer? Ah, and don’t forget warranties.

Problems of logistics and specifications are numerous, but to paraphrase my favorite midcentury cartoon character, Pogo, “We have met the future and it is here.”

I love challenges.