It almost feels like spring. People are traveling, having picnics, crossing borders, eating out, staying in hotels, building things and even taking training courses in building deconstruction and the salvaging of materials.

Seriously, in just the last couple of weeks our training and consulting arm, The ReUse Institute (TRI), has contracted to provide deconstruction workshops and worker trainings in multiple locations around the country. Ok, it might not be spring, but the increase in activity is eye-opening.

This month TRI will be presenting a two-day deconstruction workshop in Pitkin County, Colorado. Over 50 contractors, architects, county employees and other folks interested in building-materials salvage and waste diversion have signed up.

Community Development | Pitkin County, CO

Here in California, San Mateo County has also caught a bit of spring fever and is offering its second worker-training event. In 2019, San Mateo asked TRI to conduct a series of worker-training programs. The first one kicked off in May of that year, but before we could get others scheduled Covid struck and the program was put on hold. Now that things have opened up, that series is back in bloom. From Monday, November 29th through Tuesday, December 14th TRI will conduct a 12-day deconstruction training for the county of San Mateo. A major portion of the training will be devoted to deconstructing a 2,000 square-foot ranch style house in Portola Valley, California. So, if you are thinking about getting into the deconstruction and salvage business, and you work or live in San Mateo County, you might want to check out this hands-on opportunity at …

Deconstruction Job Training Course – SMC Office of Sustainability (smcsustainability.org)

The criticality of qualifying deconstruction contractors was explained in the previous installment of this three-part series. Here, I’ll explain why it is just as critical, if not more so, to qualify both the nonprofit organization (donee) and the appraiser in order to claim the highest tax deduction for your salvaged building materials.

Nonprofit Organizations

Any nonprofit with a 501(c)3 designation can receive in-kind donations—the nonmonetary kind, such as art, books, clothing, furniture and, yes, salvaged building materials. These nonprofits include organizations dedicated to religious, educational, safety and environmental purposes. The defined purpose of an organization can exempt them from federal and state income taxes. That purpose must be clearly stated on IRS form 1023 “Application for Recognition of Exemption,” which is required by the IRS before exemption is granted. The exempt purpose is often referred to as a mission statement.

Just because a 501(c)3 exempt organization can receive salvaged building materials, and provide the donor with a tax-deductible donation receipt, does not guarantee that the donor will benefit from the appraised donation value. If the exempt purpose (mission) of the donee is not to accept, use, and/or distribute used building materials, the organization must annually file form 8282 with the IRS. This form itemizes the actual revenue the organization received from the sale of the materials in question. Based on this information, the IRS has the right to adjust the donor’s donation from the appraised value to the sales-receipt value (usually lower), which increases the donor’s tax liability.

The key to obtaining the highest donation value is knowing that the donated building materials will be used in accordance with the organization’s exempt purpose. My advice? Always request a copy of the donee’s form 1023 (Application for Recognition of Exemptions) prior to making a substantial in-kind donation.

Appraisers

Any in-kind donation worth over $5,000 requires the services of an independent third-party qualified appraiser. Among other things, the word, “independent” indicates that neither the nonprofit nor the contractor has recommended any single appraiser.

Many appraisers limit their practice to either real-property or personal property, but some do both. Salvaged building materials are personal property, not real property. They have been severed from the building in reusable condition and must be appraised as personal property. Therefore, the first qualifying step is to ensure that you have chosen a personal property appraiser. However, several additional qualifying steps are important for tax-deduction purposes.

The individual appraiser has: a) earned an appraisal designation from a generally recognized professional appraiser organization; or b) has successfully completed professional or college-level coursework through an educational or appraiser organization that regularly offers programs in valuing the type of property in question; or c) has obtained the appraiser designation as part of an apprenticeship or education program similar to professional or college-level coursework.

An appraiser who has been qualified to appraise furniture is not thereby qualified to appraise art. One who has become qualified in coin collections is not qualified to appraise machinery as well. Valuing used building materials is a very specialized skill, so this type of appraiser must have a background in construction, architecture, construction estimating or something similar. Further, simply doing appraisals on one’s own does not satisfy the qualification requirements. If an appraiser claims to have received apprenticeship training under a qualified appraiser, you should contact the qualifier for verification.

Generally recognized professional appraiser organizations are typically membership organizations dependent upon member dues for their existence. They are not enforcement agencies and are usually unwilling to “eat their own.” So, while these organizations are a good place to start, do not rely on them to weed out appraisers who falsely claim to obtain the highest tax deductions for their clients.

Always ask the appraiser to show you the recently completed appraisal report of a similar client—one who made a tax-deductible donation of used building materials. When examining the report, watch out for fluff, such as sale prices of houses or other non pertinent information. Don’t forget to visit the websites of candidate appraisers to ascertain their qualifications for your type of personal property. Ask for company and individual resumes and review them for more specific qualifying information.

Donating building materials that have been salvaged through deconstruction is a smart, easy alternative to demolition. Just as when choosing an architect or building contractor, the focus should be on qualifying the candidates. This newsletter addresses the many benefits of deconstruction. The next two issues focus on qualifying deconstruction contractors, appraisers, and the organizations that receive salvaged materials, to ensure that those benefits are realized.

In the U.S. the number of single-family houses that are completely removed, whether by demolition or deconstruction, ranges from 250,000 to 300,000 per year, figures based on both governmental and private estimates. For commercial structures, the estimate is approximately 44,000 buildings. In this series I will restrict my comments to houses, and only to those that are reduced to dirt.

By various means, I would estimate that only 2,000 to 3,000 houses per year are fully deconstructed – a lowly one percent.

Sad? You bet, but there are several noteworthy reasons why deconstruction comes up short: disposal costs are absurdly low, salvage is a cottage industry with many small operators and little collaboration between them, older builders are often stuck in their customary ways, a pervasive focus on recycling tends to eclipse reuse, industry players fail to effectively sell reuse, and conflicting definitions of deconstruction confuse people, as do wide ranging estimates of price and time. Each one of these can be tough to overcome and collectively they make deconstruction difficult to sell.

Of all the benefits of deconstruction, the biggest driver is the tax benefit received by donating salvaged materials to a qualified nonprofit 501(c) organization. Still, even without tax savings, many attractive benefits accrue, including:

• Community revitalization. Donated materials help budget-minded families, first-time home buyers and owners of low to middle income rental units improve and maintain their properties.

• Reduced energy and emissions. All of the embodied energy (carbon) in salvaged materials is saved, which, by the way, is not the case with recycling.

• Reduced pollution. Deconstruction creates far less noise and dust (some of it lead) than demolition.

• Job training. Studies have shown that deconstruction employs three to five times as many people as demolition.

• Landfill preservation. New landfills almost always result in increased disposal fees.

• Historic/cultural preservation. Materials from historic buildings are reused rather than trashed.

More to come: Next month learn how to qualify competent deconstruction contractors, to maximize these great benefits.

It has been my observation that a bunch of folks involved in building-materials salvage are lumber centric.

Ask almost anyone in our business which materials they covet and you will hear something like “Lumber” or “Lumber is what my customers ask for.” I hear this over and over—even from our own employees. But wait, it gets more dramatic once the conversation touches on old-growth lumber, at which point all other topics become extraneous. Old growth lumber is limited in quantity, difficult to get and pleasing to the eye. I get it. Remember, I’m the guy who two months ago wrote The Velvet Crowbar blog entitled, “Musings of a Lumber Hugger.”

But, what about all the other stuff—appliances, bricks, cabinets, doors, windows? There is a demand for those materials too, so let’s look at the markets and advantages of lumber vs. fixtures.

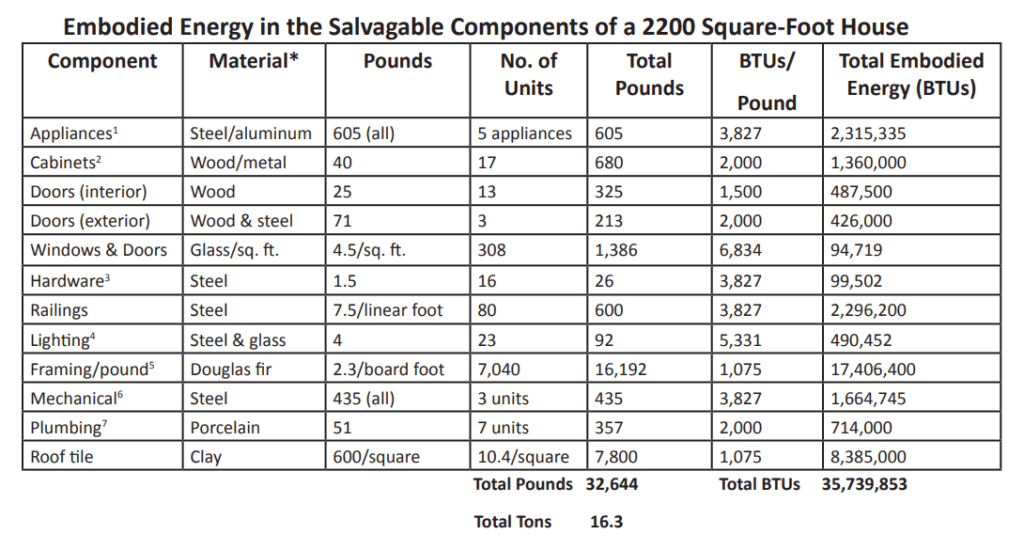

I was recently asked to conduct a 90-minute webinar on Life Cycle Assessment and, consequently, needed to do some research. I decided to focus on embodied energy. The whole notion of the energy it takes to make something intrigued me, especially since TRP was part of a study on the topic by Forest Products Laboratory. My investigation led me to the book, Stewardship of the Built Environment, by Robert A. Young in which he charts building materials and quantifies their embodied energy in BTUs per pound.

Using Professor Young’s research, I looked at my own house as a deconstruction candidate and calculated the embodied energy for each component that would normally be salvaged.

Below is a chart of those materials, their quantity, weight and the embodied energy in each. What becomes apparent is that while lumber has the lowest embodied energy per pound, the total energy in the quantity of lumber salvaged is the highest of all the materials that would normally be salvaged. Yet, it only totals 49% of the embodied energy in those materials. I realize that most houses do not have clay roof tile (mine does) so I removed its embodied energy from the calculations and then the lumber equaled 63% of the total.

Looking at the broader picture, here are some other points that make lumber less attractive than claimed:

• Non-lumber materials are easier to remove and require less work (energy).

• Lumber is salvaged only after all other materials have been salvaged, recycled or landfilled. This salvaging process alone involves more embodied energy than removing a cabinet, toilet or door.

• Just because lumber is in high demand does not mean there are no after-markets for the other materials.

That would be like saying the only demand for used automobiles is for BMWs. TRP offers firsthand proof of this: historically our annual lumber sales represent 25 to 30% of our total retail sales, yet sales over the past 12 months have been the highest in 28 years, and lumber sales represented only 15% of sales during that period.

• Merchandising lumber is more difficult than other materials: lumber price points vary depending upon species and age, some customers buy individual sticks and others want entire units, and each lumber sale requires different handling requirements.

Extrapolating from TRP’s own 2010 through 2020 data, only 25% of TRP projects are full deconstructions (including lumber). The rest are remodels. Of the 200 projects whose materials come to our warehouse, or are delivered to a partnering warehouse each year, only 50 include any significant quantity of lumber. This means the vast majority of deconstruction projects reclaim only fixtures.

Is lumber important in the salvage business? Of course it is, but there are outstanding sales opportunities in other materials. And, if your focus is on the environment, then energy (read carbon) per pound is important. More energy is saved through the salvage and reuse of those other materials. Finally, as any good retailer will tell you, stocking a variety of materials draws more customers and hence results in higher sales than positioning yourself as a strictly used lumber yard. That’s one reason why commercial lumber yards carry all sorts of hardware, fasteners, tools and other non-lumber items.

Footnotes * All metal is considered recycled – Otherwise virgin steel would be 13,760 BTU/pound and aluminum 97,610.

1. Stove with cooktop, 2 refrigerators, microwave, dishwasher

2. Cabinets are an enhanced wood product with metal pulls and drawer slides

3. Door knobs, hinges, faucets

4. Assumed each fixture contained equal weights of steel and glass

5. Assumed 17,600 board feet of Douglas fir (EPA estimates are 16,000 for 2000 s.f.) with a 40% salvage rate

6. Furnace, compressor and water heater

7. 3 bath sinks, 2 toilets and 1 laundry sink. Estimate of BTUs for porcelain is mine.

With the entire country in a bit of a real estate frenzy, houses that are for sale often vanish soon after escrow closes, only to be replaced something entirely new. Here’s a way that both buyers and sellers in such transformations could benefit.

The real estate agent is often the first person to recognize that a listed home is a candidate for replacement. Of course, the agent’s hunch can’t be confirmed until a buyer is secured. But assuming the agent is correct and the house is coming down, all three parties (seller, buyer and agent) could benefit by taking a few simple steps.

First, the purchase agreement would need to be written to allow the seller to deconstruct his or her own home, leaving the underlying real estate ready to receive whatever replacement the buyer intends to build.

Second, the seller, working with a TRP manager or other skilled reuse professional, would need to obtain a survey of the property detailing, in writing and photos, all the materials to be salvaged for reuse, including framing lumber. The survey results would be sent to several IRS-qualified appraisers who would, at no cost to the seller, calculate estimates of the donation value the seller would receive upon deconstruction and donation of the materials. From these estimates, the seller would ultimately choose one appraiser to work with. The seller would also obtain a bid from a certified deconstruction contractor to carefully remove all the materials indicated in the survey and deliver them to a qualified nonprofit organization, such as TRP.

Third, once such project details are agreed upon, the chosen appraiser would visit the site to inspect the materials, and the nonprofit would create descriptive inventories of all of the materials.

Fourth, upon delivery of the salvaged materials, final inventories would be created based on what was actually received by the nonprofit. These final inventories would be sent to the appraiser, who would complete an appraisal report and deliver it to the donor, along with all required IRS forms.

Fifth, escrow would close, the buyer would take possession of a clean lot, and the seller would receive a substantial tax deduction.

As you can see, the process is straightforward and delivers the following benefits:

• The seller obtains a great price for the house and a substantial tax benefit.

• The buyer receives a build-ready lot, without having to pay for demolition.

• The real estate agent earns kudos from the client, and has mastered a new sales tool.

Note: Deconstruction typically costs more than demolition. If the seller did not have funds available for this type of transaction, the buyer could sweeten the deal by offering to fund a portion of the purchase price through escrow, and before closing, to pay for the difference.

By the way, this process works for remodeling projects as well.

I receive several calls a week from building owners who want information on a variety of topics related to deconstruction and its benefits. Mostly, they ask which contractors are qualified to do deconstruction.

While I know of contractors in the cities where TRP has regional associates, I’m at a loss to help owners in other areas. To help, I’ve decided to provide a list of criteria for selecting deconstruction contractors, in the hope that having a basic profile will allow building owners to vet their own.

I think it best to start with the goal, or objective. In deconstruction, the goal is to end up with a group of salvaged materials that can be made immediately available for reuse. Whether the owner is motivated by a desire to reuse some of the materials in the new project, or by the tax benefits of donating to a qualified nonprofit organization, or simply by knowing it’s the right thing to do, all salvaged materials need to be in reusable condition, otherwise the process and expense of deconstruction is for naught.

Having worked with numerous general contractors, builders and remodelers over the past 28 years, I’ve learned that, if a contractor is competent with all manner of tools and equipment, I don’t need to tell them how to deconstruct anything. However, what must be made perfectly clear is how the materials must look and perform after they are salvaged. Each contractor has their own way of doing things. My job, or the owner’s job, is to insist on how and in what condition the materials must be when made available to the next user.

How can you ensure that a contractor is both willing and able to achieve this goal? By applying the following criteria to your search.

• Is the contractor properly licensed and competent in accordance with city/state requirements?

• How many deconstruction projects has the contractor completed in the past year?

• Insist that the contractor show you certificates of insurance for general liability, vehicles, and workers compensation, with at least $1 million coverage on each.

• Insist on receiving at least three references from recent deconstruction customers.

• Find out where and how the materials will be distributed.

An aside: If drivers’ licensing were based on true competency, there would far fewer automobile collisions and deaths.

Often, a demolition contractor will assure you of their ability to do deconstruction. Be very skeptical of this claim. In my experience, while most demolition contractors know how to demolish a building, they know very little about deconstruction techniques. Contrary to popular belief, deconstruction is not simply a subset of demolition—or of recycling. It requires completely different skills and knowledge in every respect except one: At the end of the process, the building, or parts of the building, will be gone from the site.

In recycling, the form (and often the function) of an object is going to change. It will be broken apart or ground up—in some way reprocessed. In reuse, the object does not change. So, to ensure that all materials are handled for reuse, not recycling, tell the selected contractor what condition you expect the materials to be in when the job is completed.

Here are three examples:

Kitchen cabinets: Ensure all doors and drawers are intact and in place, all exposed nail and screw points are removed, and each cabinet is shrink-wrapped prior to transport.

Light fixtures: Must be wrapped for protection and placed in individual cardboard boxes.

Doors: Each must be treated as a pre-hung door with the strike-plate side of the jamb screwed into the edge of the door between the door knob and the bottom of the door.

These are merely examples, possibly enough for a kitchen remodel. Extensive projects require a far more extensive list, which I am happy to provide. Just send me an email request. TedReiff@TheReUsePeople.org Questions are welcome too.

Here’s to good vetting!

Many municipalities are currently considering the adoption of landfill-diversion ordinances requiring deconstruction. The driver of these initiatives is environmental, and they are often promoted by zero-waste organizations. Such ordinances have numerous benefits and beneficiaries. Generally, they …

• Relieve overburdened landfills

• Provide alternatives to the purchase of new materials for home improvement and construction projects

• Save enormous quantities of embodied energy

• Increase economic development in communities

• Foster new employment opportunities

• Reduce noise and dust pollution

• Preserve resources

• Allow historic preservation

• Incentivize private building owners

And undoubtedly I’ve missed a few.

While the benefits are many, the process of getting salvaged materials from deconstructed buildings to consumers requires careful coordination through the entire supply chain. At least five distinct players are necessary to achieve that objective. Below is a quick review of the process and players, beginning with buyers and going back to the origin of the materials. For simplicity, the focus is on residential structures only.

Buyers. Potential buyers need to be numerous enough to consume the volume of materials that the ordinance is intended to provide. With minor exceptions, this level of absorption can only be accomplished in population centers of a half-million residents or more.

Retailers. To meet the requirements of an ordinance, a full spectrum of materials must be salvaged—not just Viking stoves, Marvin double-glazed windows, or old-growth lumber. This spectrum includes single-glazed windows, hollow-core flush doors, blue bathroom fixtures, laminated kitchen cabinets—maybe even MDF trim (yuck!). Consequently, the store needs to be large and capable enough to handle the full range of reusable building materials, with neither restoration nor repairs. While wood is the dominant material most salvagers are after, it also has the lowest embodied energy of all reusable building materials, by a factor of three to ten times. Consequently, retailers must provide a complete, precise inventory of all materials received pursuant to the ordinance. Further, the weights of the salvaged materials must be gauged, because without weights and inventories there can be no accuracy or accountability.

Deconstruction contractors. In the commercial market these might be demolition contractors, but I’ve rarely seen a demolition contractor do a competent deconstruction job on a residential structure. Some municipalities require contractors to be trained in deconstruction, but training doesn’t guarantee competency. Selecting a contractor is like buying any high-end item. It rests on research, referrals and references. Caveat emptor!

Building owners. Blighted and abandoned houses yield lumber, but rarely satisfy the demands of the broader used-materials market. A residence lived in and maintained that is to be renovated or removed will yield more and better materials. And almost any owner remodeling or tearing down an entire house can afford deconstruction because they:

• Have a high enough income to claim tax benefits from donating their salvaged materials.

• Have already experienced a 150% increase in the cost of framing lumber and other wood-made products, plus cost increases for electrical, HVAC equipment, plumbing, windows, various building permits and utility connections. The modest difference between smash-and-dash demotion and deconstruction is, by comparison, minimal

Deconstruction & Salvage Surveys. Prior to any deconstruction project, a survey should be completed enumerating and describing each and every element to be salvaged. This single task is the glue which holds the entire enterprise together. Without it, potential buyers will not know what is available, stores will not be prepared for what is coming, deconstruction contractors will not know what or how much to salvage, and owners will not know what is donatable. To be effective, the survey should be completed by the store receiving the materials, since the store, through experience, knows which materials the community demands.

While all of these factors are necessary for an ordinance to be successful, the key player is the all-accepting store—and the key tool is the survey. Municipalities can’t claim to have met their objectives without measuring performance, and the survey is the yardstick by which deconstruction is measured.

If you are interested in a deeper dive into this type of ordinance, email me. I will send you my white paper on Deconstruction Ordinances. TedReiff@TheReUsePeople.org

First, I have to admit that I am not a woodworker, nor do I have a woodshop in my garage. However, I do love wood. I always have.

I first appreciated the beauty of wood while admiring sculptures carved by my uncle, Bob Knauer, who, in his sophomore year, placed third in a juried show at the Cleveland Institute of Art. His entry was a sculpture of his left hand carved from exotic wood collected during his travels as a WWII foot soldier. For my eighth birthday, he gave me a 15-foot high, hand-carved totem pole complete with winged beasts and other critters. (I always accused my older sister of modeling for one of the beasts.)

Now, more than a half a century later, I am in the deconstruction business salvaging lumber—among other things. While I get a kick out of seeing an old craftsman window, or a beautiful 1930s porcelain pedestal sink, seeing a unit of old 2x8s salvaged from a deconstructed house really turns me on—weird huh? I guess it’s the memory of those beautiful things Bob carved that gets me imagining the next life a piece of that lumber might have. Windows and sinks don’t have much choice in their afterlife. They may be used as decorative hangings or planters, but their form doesn’t change. A chunk of lumber has infinite possibilities.

TRP sells the lumber from deconstruction projects into a myriad of markets. Sometimes a chunk of lumber becomes a framing member in a remodeling project. Truthfully, that’s probably where the vast majority of lumber goes. Even without the proper grade stamp, salvaged lumber can be used for framing, as long as it’s a non-structural element, or if the local inspector or structural engineer signs off on its use. But even the lowly 2x4 can generate some excitement. It might go into a new green construction project, or wind up as part of a decorative display in a LEED Gold building, such as the project we did at Texas State Technical College in Harlingen, Texas.

Other uses are more glamorous, of course. Talented woodworkers turn our old growth, Douglas Fir into beautiful furniture. A mill produces tongue and groove flooring from some of our lumber. A post-and-beam builder uses larger dimensional beams in the construction of new custom homes. Old double teardrop and shiplap redwood siding is often expertly resurfaced to match the siding on existing period homes.

Straight-grained Douglas fir and maple bowling alley lanes and gymnasium floors have wound up as floors, tables, countertops and bars from Ketchum, Idaho, to North Haven, Connecticut—from Bahia de Los Angeles in Baja to the Tonga Islands and beyond for all I know. Still, for me, it doesn’t matter the species, dimension or grade. It’s wood, it’s got warmth and its going to serve another great purpose for someone, somewhere. So, for a former investment banker what’s the bottom line? Hell, I don’t know, but for an old lumber hugger it means a great big smile and maybe another story.

In a recent news article I read about a magnificent 1854 Greek revival house in the Midwest that had been torn down to make room for a parking lot! Though it was owned by local government, no one, not even the historic preservation commission, was allowed to salvage the building’s artifacts. Instead, this two-story marvel, with walnut staircase, floral motifs, cast iron mantel and countless other treasures became a pile of rubble.

I got to thinking of the salvaged materials TRP received from the deconstruction of Ray Bradbury’s home in Los Angeles. We turned the 2x6 tongue-and-groove roofing into 451 sets of bookends (as in Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury’s most famous book). Within two weeks we sold all but two sets for $85.00 each. TRP retained two sets and donated one plus a check for $1,000.00 to the Ray Bradbury Institute at the University of Indiana.

With these two incidences in mind, I think both professional and amateur preservationists will understand that there is more to preservation than saving buildings. When the opportunity to save a whole building is thwarted by the community, city, or courts, and a cherished structure must come down, one preservation alternative remains: salvage its parts.

When the components of a significant building are preserved through deconstruction, people have the opportunity to acquire a piece of history. The issue of expense invariably arises because deconstruction costs more than traditional smash-and-dash demolition. However, if adopted, the following scenario would mitigate the additional expense and enhance the coffers of local historical and preservation societies.

A company of talented and certified deconstructionists is hired to slowly and methodically take the building apart, board by board, piece by piece, making its individual elements available for purchase and installation in other buildings -- public or private, residential or commercial.

TRP works with a number of certified deconstruction contractors and is familiar with others around the country. Any one of these companies could form a Rapid Deconstruction Strike Team willing to deconstruct the building for the demolition cost specified in the permit already in hand. Following deconstruction, TRP, with assistance from local historical groups, would authenticate the salvaged materials. This would in most cases substantially enhance their sale price, as occurred with the Bradbury house (in that instance, Bradbury’s daughter signed the letter of authenticity). This extra value would be used to compensate the deconstruction contractor for the difference between the deconstruction cost and the demolition price previously received. Any balance could then be donated to the historical group that helped to establish provenance.

Call me when you see a historical building being relegated to the landfill.